|  |

A story from history, told by Choral Pepper; edited by David Kier

The incredibly blue sea we call the Gulf of California has laid claim to names far more romantic than its present one. Early Spanish explorers who sailed northward in 1538 as far as Cedros Island called it the “Sea of Cortez” to honor the Spanish explorer of Mexico. Later explorers, some of whom were jealous enemies of Cortez, changed its name to the “Vermilion Sea” because of the red tint from Colorado River runoff. Shipwrecks, mutinies, a fabled island dominated by Amazons, political disputes, pearl fishermen, smugglers, piracy-- all are part of the Gulf’s oft-told legendary history, with one important exception.

While I researched old records for my early Baja book, the name “Ocio” cropped up in so many instances that it piqued my curiosity. The man appeared to be an enormous power, and yet nothing of substance gave a concrete account of his activities. I could not decide whether he was one of the “good guys” or one of the “bad guys,” so I began to fit bits and pieces of information together.

Manuel Ocio was a master at delivering the shaft. He not only pulled off the biggest mine swindle in the history of Baja California, but he also expedited, if not directly brought about, the expulsion of the Jesuit Order from the New World.

Ocio arrived in Baja California as a mission soldier. Almost immediately he recognized that a future in pearl hunting would be more lucrative than one in soul saving. When a band of recently converted Indigenous divers arrived at San Ignacio Mission bearing a cache of pearls destined for the Holy Virgin, Ocio managed to intercept their leader and for a trifling value, acquire the pearls. With this grubstake, he procured a discharge from the mission army and hastened to Sinaloa on the mainland to purchase boats, supplies and men.

By 1742, Ocio had fished up more than 128 pounds of pearls. By 1744, his record exceeded 275 pounds per year. He then produced a coup that forever established him as the Pearl King of Mexico. Off the shore of Mulegé, his Yaqui divers brought up the largest pearl ever found in peninsular waters -- a giant the size of a pigeon egg valued at 50,000 pesos. Ocio offered to sell it to the Queen of Spain, and she accepted his offer. This established him as Mexico’s leading pearler and gained for him the fawning respect of Spain’s governing body in the New World.

Conversely, it repulsed the Jesuit fathers. Five percent of all pearls acquired by legitimate pearl hunters went to the Crown, but only after the largest and most perfectly formed had been collected by the priests to be set aside for the Holy Virgin. That Ocio had ignored this tradition did not endear him to the clergy. They showed their displeasure in 1750 by outlawing all pearl fisheries in peninsular waters because pearl hunters and corrupt mission soldiers were arousing discontent among the converts and causing uprisings.

The powerful Jesuits, in their agreement with the Crown, were empowered with full rights of administration in Baja California provided they operated there at their own expense. So, there was little that Ocio could do but continue his fisheries surreptitiously. This he managed to do for good many years until a fateful encounter inspired him to take on the Jesuits in a new endeavor.

While on a business trip to Guadalajara, Ocio met a priest, a Franciscan, with whom he could talk sense. This man resented the power that the Jesuit order held in Baja California almost as bitterly as did Ocio. He pointed out that although the Jesuits were empowered with full rights of administration on the peninsula, possession of the land still remained in the name of his Majesty. Considering Ocio’s popularity with the king’s advocates in the New World, would it not be possible for him to acquire from the Crown land capable of being developed for mining? Surely the Crown would prefer mining interests to be in the hands of a trusted citizen rather than controlled by the secretive Jesuits.

Ocio laid his plans well, carefully, and slowly. He acquired a powerful business partner in Guadalajara to negotiate on their behalf on the mainland, while Ocio himself returned to Baja California to study the land. As a blacksmith in his youth in Andalusia, he had learned enough about metallurgy to convince himself that a weak silver lode lay in the Santa Ana district near the southern tip of the peninsula. This area also embraced plentiful grazing land for cattle and had a convenient access for shipments arriving by sea. Although it was situated between two missions, Santiago and Todos Santos, it was still isolated enough to minimize Jesuit interference with the Indigenous miners. That prospect, however, was eliminated in one forceful blow when the Jesuits issued an order that no Baja California native would be permitted to work in Ocio’s mines.

This injunction deterred Ocio only temporarily. He still maintained a fleet of ships that employed Yaqui divers who could be brought from Sonora to work the mines. They also could cause unrest with the Jesuit’s converts, he ultimately learned. Ocio’s miners were building up resentment among Baja Indigenous by telling them that natives on the mainland were given their own land to cultivate as they liked, keeping all profits to themselves. This caused the mission’s fickle-minded Pericus to make extravagant demands upon the missions, even though the claim was not true.

Jesuit missionaries further complained that Ocio did nothing to provide for the spiritual needs of his laborers. When out of charity they felt compelled to visit the mines to celebrate mass, Ocio refused to compensate by even providing meals or paying traveling expenses.

Then new problems arose. Santa Ana’s miners ran short of supplies and took advantage of the priests’ compassion by applying at Santiago and Todos Santa missions for help. The missionaries naturally did not wish to sell provisions, that they needed for their own converts, but with the poor miners so neglected by their employer, it seemed cruel to refuse them. To solve the dilemma, the priests took to charging a just price to those who could pay while others received necessary supplies for free.

As Ocio had designed it, word soon reached Jesuit enemies in Mexico that corn, and other produce sold to the miners at the mission instituted a great commercial enterprise in which the missionaries acted as agents. This accusation was accompanied with another claiming that the missionary at Santiago was also engaged in furnishing fresh provisions to the Manila Galleon that annually entered the harbor at San Bernabe.

Meanwhile, following the Jesuit ban on pearl fisheries in 1750, Ocio subsidized the development of his Santa Ana property by making ninety-day voyages every few years to Europe in order to profitably unload his illegally obtained pearls. On one of these sojourns Don Jose de Galvez, an aristocrat whom King Carlos III was secretly planning to send to rule New Spain, sought him out. Ocio discussed quite frankly his concern over Jesuit exploitation of the Baja California peninsula, emphasizing that their continual interference impeded the progress of his mining industry. Don Jose listened sympathetically.

A short time thereafter the superior of the Jesuits in Mexico found reason to fear that enemies of the Order, specifically one, prevented from enriching himself at the expense of peninsula natives, were attempting to falsely pin a crime on the priests who charitably visited his mines. To prevent this from occurring in the future, the Superior demanded that Ocio obtain a secular priest to serve his mining settlement.

Paradoxically, Ocio welcomed this idea. He had a son approaching marriageable age that had grown up under the tutelage of ignorant cowhands and miners. Ocio himself had felt inadequate to certain social situations during his visits to the mainland and he was desirous that his son and heir make a worthy marriage and be equipped to cope with the new station in life to which the family had ascended. Possibly an educated priest familiar with the social amenities of the mainland would be an asset to Ocio’s establishment. So, for once Ocio agreed with a Jesuit command provided he selected the priest.

This was agreed to, and Ocio sailed to Guadalajara. He returned with a priest whose name was never known outside of Ocio’s household. Where the priest went when he departed two years later was never revealed. During the priest’s stay, however, Ocio accomplished his purpose. His son was wed to the daughter of a highly respected merchant and business associate of his father’s after a dowry of 20,000 guilders from Ocio’s European pearl profits had persuaded the girl to come to Baja California.

Following the priest’s unexplained departure, the little chapel at Santa Ana stood empty and the disagreeable task of saving uncouth miners’ souls again fell upon the missionary at Santiago. With it also came the necessity of providing for their substance when supplies ran short at Ocio’s company store, an occurrence that grew alarmingly frequent. Increasing likewise in frequency were whispers on the mainland that the Jesuits were undermining Ocio’s control over his mine workers and retarding production that resulted in a loss of tax revenue for the Crown.

The whole business climaxed in 1767 when the first party of Franciscan priests set sail from the mainland in a launch provided for them by Don Manuel Ocio. They were enroute to Baja California to replace the Jesuits, who had been expelled by a secret mandate from Spain.

Two years prior to that, Don Jose de Galvez had arrived in New Spain, endowed by King Carlos III with almost absolute power. One year following the Jesuit expulsion, Don Jose himself arrived on the peninsula. He, too, sailed there in a ship owned by Ocio and when he and his family arrived, they proceeded directly to Santa Ana where they lodged with Ocio while Galvez set up headquarters from which to start colonization.

Galvez was intensely interested in colonizing Lower California with Spaniards. He was still convinced that great riches lay somewhere in the land and with so many missions losing converts to epidemics, he wanted to make sure that the Crown maintained its foothold there. At least, that appeared to be his motive when he separated government land from mission land and offered it to mainland Spaniards of good reputation on easy terms.

A district was organized called “Real de Minas” with headquarters in Santa Ana. It was this district that was settled first to the gratification of Ocio, who owned the only store in the district. Supplied with meat from his own cattle that grazed on his own land and other goods that arrived on his ships from the company he owned in partnership with his new daughter-in-law’s father in Guadalajara, the store’s profits increased with each new arrival.

Even Ocio’s mines appeared to prosper with the exodus of the Jesuits. For the first time, the viceroy in Mexico began to receive bars of silver designated as the Royal Fifth. The viceroy also received tokens of pearls from Galvez, with a vague explanation that they were mined during his stay on the peninsula.

Things began to look so profitable on the peninsula that when Ocio suggested one day that he might be talked into selling his mines to the Crown, Galvez offered to cooperate. Or perhaps Galvez had offered to cooperate long before. At any rate, toward the end of Galvez’ yearlong residence with Ocio, the sale was consummated. Houses were added for dependents in the royal service, the chapel was enlarged with intentions to raise it to the status of a mission, and Ocio’s mercantile operation was doing a thriving business supplying the new settlers. Galvez then sailed back to the mainland, leaving his secretary, Juan Manuel Viniegra, to oversee the completion of the project.

Viniegra did not have to remain very long.

By 1771 the proposed mission at Santa Ana had been abandoned. Indigenous people brought over from Sonora to work the mines had been returned to their respective pueblos to relieve the Crown of their support. The mine was ordered sold, along with everything pertaining to it. If a purchaser could not be found, the mine was to be given to anyone who could work it. There had been no further receipts for the Royal Fifth from Santa Ana after the mines had been purchased from Ocio by the Crown.

Father Francisco Palou, a Franciscan priest asked to report on the situation, wrote that a man versed in such matters had informed him that the mines were of so little value that they had never paid their way, even when Ocio had them. Later, Galvez’ secretary, Viniegra, confessed that no metal was ever refined from the Santa Ana mines, but that the bars of silver and the pearls sent to the viceroy in Mexico by Galvez had been taken from the missions after the Jesuits departed.

In a surprise move to discount these rumors, Manuel Ocio leased back from the Crown a part of the abandoned mines, but the move was suspected as a ploy to disguise his profits from illegal pearl fisheries.

The small chapel still stands at Santa Ana, along with ruins of Ocio’s mansion. The settlement is a ghost town, haunted by a legend that lives on in distant Guadalajara.

According to this legend, Ocio was killed by his Yaqui pearl divers while getting ready to take five hundred pounds of pearls to Europe to sell. While he prepared for his voyage, the pearls were believed to be buried for safekeeping at the mine property he had recently leased from the Crown at a site called “Tescalama.” His son had already moved from Baja California to continue family interests in Guadalajara.

The pearls have never been found.

Juan de Iturbe, explorer for the King and pearler on his own account, sailed the entire length along the California Gulf Coast and into the Colorado River in 1615. After loading his fifty-ton ship with a great fortune in pearls, he sailed northward beyond San Felipe, but instead of finding the mouth of the Colorado River, he discovered himself grounded on a sandbar in a vast sea surrounded by mountains. Certain that he had discovered the long-sought Straits of Anian that gave entrance to the Pacific Ocean, even though it had already been determined that this was not so, Iturbe stayed there for a month waiting for a storm or enough wind to carry him off the bar. At last, the heavens favored him with a great cloudburst, but water gushed down from the high mountains with such fury that waves rendered his ship unmanageable.

Still dreaming that he and his crew would be ennobled by the King and endowed with measureless fame and fortune, Iturbe continued his exploration by land. When supplies ran low, they dried flesh from antelope and wild sheep. After several months of futile searching, they climbed to the top of the highest mountain and identified the Colorado River winding toward the northeast, but the mouth of it was as elusive as the supposed Straits running to the west.

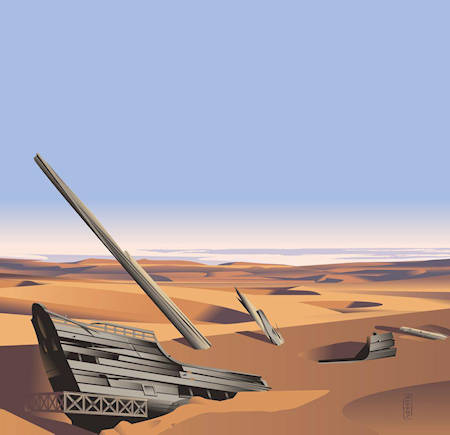

With their ship finally seaworthy, they attempted again to sail around the landlocked sea in search of an exit, but somehow, as if controlled by a sorcerer, the water had receded. Iturbe once again found himself grounded, this time on soft, boggy ground from which the crew barely escaped alive. With little choice, they abandoned the ship with its vast treasure of pearls, leaving it poised upright with its keel buried in sand as if a-sail, and managed to straggle across the sandy waste back to the Gulf where they eventually were rescued.

Iturbe’s aborted pearling adventure gave birth to one of California’s greatest lost treasure legends, The Lost Ship of the Desert.

Read more about Ocio and the Real de Santa Ana.

Read more about Choral Pepper.

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler, author of 'Baja California - Land Of Missions' and co-author of 'Old Missions of the Californias'. Visit the Old Missions website.

seemless

Fabulous service. The video to get to the San Ysidro/Tijuana SENTRI lines was perfect and peace of...

Fast and easy every time. Saves your Vehicle information to make it easy for future purchases.