|  |

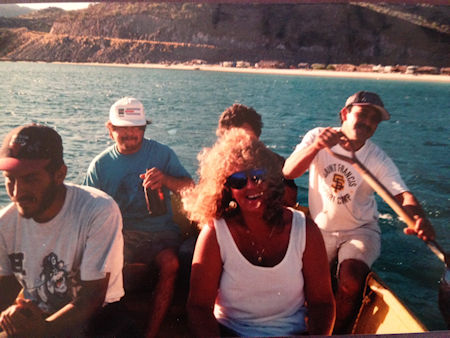

In 1994 my sister, Alisabeth and I had traveled to Mulegé in my 1973 Super Bug. We stood on the shore watching as the sunlight danced across the Bay of Conception as a panga was coming into shore. A day earlier while eating tacos in a little palapa near the lighthouse we happened to meet the crew of El Joven, a fishing trawler out of Guaymas. We received an impassioned plea to join them for a night of shrimping. Against my better judgment, Alisabeth convinced me it would be an experience of a lifetime. Chamula, the Captain of El Joven, pulled the panga up on the rocks and called to us. He was dark skinned and quite striking wearing Ray-Bans sunglasses, cutoff jeans, and a Panama hat. Once we were settled, he pushed off. He opened the throttle on the outboard and the rear of the panga settled into the sea as the bow lifted slapping against the swells. Boarding from the panga to the larger trawler was quite a feat, because both objects were moving at the same time but in different directions. I gripped the rusting rail at the exact moment the panga rose and the Joven remained still, I flung myself up and over as if mounting an uneasy horse. There I was straddling the railing, wondering what to do next. One of the crew reached out to help. As my feet touched the deck it lifted and threw me off balance. So, I rather fell into the festivities, but no one seemed to notice the lack of grace.

Dripping wet nets hung over the deck, fanning out from the gunwales, ready for the night’s work. The aging steel decks rocked gently with the swells of the Gulf waters. Dried fish-smell assailed the nostrils from forgotten creatures caught in the corners, which had escaped the morning hose down. The salty smells and gusty laughter of the Mexican seamen made the scene surreal. I looked out over the water wanting to capture every detail; the lobos or sea lions, rolled lazily in the water, flippers raised to the sky. One young crewman, Freddie, took us down into his engine room. Proudly he displayed the heart of the Joven. Everything was well maintained. He started the maquina while we watched. An ear-splitting roar filled the small engine room, followed by the thundering clatter of pistons and gears.

Climbing back out of the hold in the early evening sunshine, we started to prepare for the adventure. I felt like we were on assignment for National Geographic entitled “How shrimp find their way to your cocktails.” The anchor was dragged from its depths. Alisabeth and I watched in fascination as the crew handled the heavy cables and ropes. There was no stress in their action. It was one fluid synchronized motion.

We stood with Chamula at the helm. The sea was calm, glassy, and the ship sliced through its stillness. The nightly routine began. The nets were dropped just outside the protected coastline a short time after dusk. Shrimp slept during the day and fed at night. The heavy nets disappeared below the surface as trolling for the shrimp began. One small net called a “chango” or monkey, was used to check the catch before bringing up the two larger nets. When the count in the little chango was ten or more the other nets would be hauled in.

Piloting in S shape patterns across the Gulf waiting for the count, Alisabeth and I took a walk about the deck. Leaning over the railing I watched a school of dolphin move in and out of the bow wave shimmering in the phosphorescent water. I watched one that kept turning on its side looking up at me and I swear this isn’t an old fishing tale. When it was time, the men took their places. Two men were on each side of the nets and two men handled the winches. Heavy groans issued from the straining cables as they brought their prize to the surface. The first time I saw the heavy nets swing over the deck, I was stunned. I had not expected this. The marineros pulled the heavy ropes and released a mountain of living things; besides the shrimp, all kinds of bottom fish, starfish, small shark, sea snails, shells, crab, and eels. All were dumped in a writhing mass on the deck.

My sister and I didn’t know how to feel. This was a livelihood for these men and their families. The whole world wanted shrimp. We were horrified to witness the destruction of the sea bottom. I had to ask myself, would I give up my shrimp tacos to save the Gulf of California’s sea life? Would anyone? The deck crew began to work the haul after securing the ropes and cables. With primitive wooden tools, they began to sort through the carnage, separating the shrimp, and throwing them into large wicker baskets, where they waited to be washed and de-headed. The edible fish were tossed to the side and would become breakfast or dinner. The rest of the mass became food for the sea birds.

This ritual of gathering would be done three times during the night. Sleep for the crew happened between the nets being pulled and after the sorting. Alisabeth and I tried our best to fit into this sleep pattern. I was completely surprised at the ease with which I dropped off into deep sleep. Maybe it was the rocking of the ship and the pounding heartbeat of the maquina. It was like crawling into the lap of a giant mother whose job was to watch over me.

Near dawn, and slopping coffee, I made wobbly progress to the helm. It would be hard to describe the soft beauty of the morning. The men started pulling on their yellow slickers and headed out on deck, rubbing sleep from their eyes. I could hear the growl of the winches as they strained to pull in the nets. Like magic, the sky began to fill with circling birds; black shapes against the rising sun. Their numbers increased to nearly swarm proportions. They knew the feast was certain. The sun rose out of the water.

Alisabeth joined me on the stern to watch in utter astonishment as the mound of undesirable sea life was pushed overboard to become the morning meal for the winged-ones. Brown pelican, great frigate birds, sea gulls and terns in one swirling body began to dive on the first shovelfuls. The wild screeching filled our ears. Their bodies smashed into each other and into the churning sea. As magically as they filled the sky, they were gone seeking out the next incoming shrimp boat.

With a huge hose, the decks were washed down and all the baskets of shrimp were gathered together and rinsed down as well. The men pulled up the short wooden stools and began ripping the heads from the bodies. Twist. Toss. Twist. Toss. The heads went into a pile and would be given to the local pescador’s for bait. The shrimp were processed according to size. We were told that the United States would never see the largest shrimp because these were sent to Japan. We were invited to join in. It wasn’t the easiest thing I’ve ever done on my Baja adventures, but spurred on by the great Mexican humor, I did my first twist, and off came the head. Chamula offered me a gooey orange mass saying it was shrimp brains, I gagged, and declined; he laughed. At 9:00 am nets stowed and the cook called everyone in for breakfast. As Alisabeth forked in a mouthful of fresh fish, she looked at me in wonder, “An experience of a lifetime?” I sighed, “Yes, an experience of a lifetime.”

It was simple to purchase coverage and feeling that I was protected.

I can't think of an easier way to get Mexican insurance; just one call on my departure day and I...

Third time working with Baja Bound and they made it easy! Thanks!