|  |

By Greg Niemann

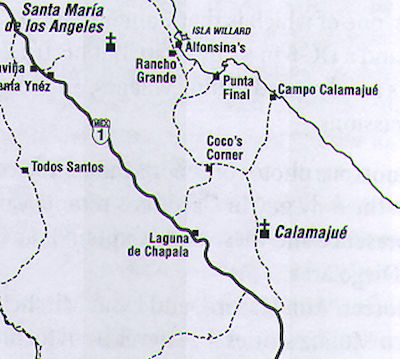

Back in 1996 Ken and I headed up the rocky old mission trail road to Calamajué in his Toyota pickup. From the mission site and then Campo Calamajué we planned to backtrack to Coco’s Corner and eventually join the road through Gonzaga Bay up to San Felipe on our loop back to Ensenada. (Much of this trip is today’s Mexico’s Highway 5).

I'd been through the Calamajué mission road twice previously in my Jeep. But those were summertime trips and the roadbed stream was only inches deep. This time it was December and an earlier storm had caused the intermittent stream to swell.

From Highway 1, 13 miles north of the Bahia de Los Angeles cutoff, the road took off up a narrow, sandy wash, and then went through the desert to the east. It turned northward, among a thickening forest of large, multi-armed cardon cactus and huge twisting and bending cirio trees, their bright winter blossoms adding a bit of color to the barren desert.

With intense concentration on the road, Ken barely noticed the abundance of flora in the area as he maneuvered ruts, patches of thick sand, and occasional rocks. I realized my off-road objectives are different from his.

I most enjoy where the roads take me. And I love to soak up the beauty, or uniqueness of the wild country I drive through.

On the other hand, Ken likes to attack a road and “flat out” best describes his dream speed. This time he sensibly tempered his speed a bit with me along.

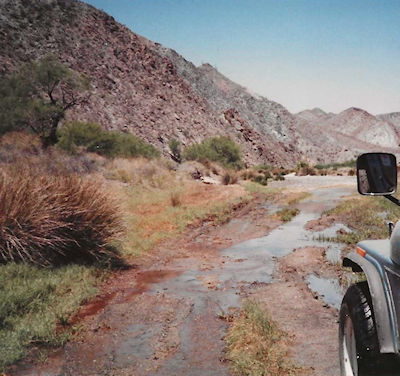

I said little, just watching the desert fly by and holding my sides tight lest I suffer bruised ribs and damaged organs. He was forced to slow down once we dropped into the Calamajué canyon. Year-round springs fed the valley floor with a trickling stream, adding palms, swamp grass, and small shade trees to the harsh landscape. The road follows the stream bed, and numerous times we'd splash through water while clumps of swamp grass nearly obliterated the road and scraped both sides of his truck.

A few cows grazed in the area, especially as the canyon widened and green meadows replaced the sandy desert floor. I noticed little change in the years since I was in the area last, but change is slow in these remote arroyos of the Baja peninsula.

The Meadow Was a Muddy Swamp

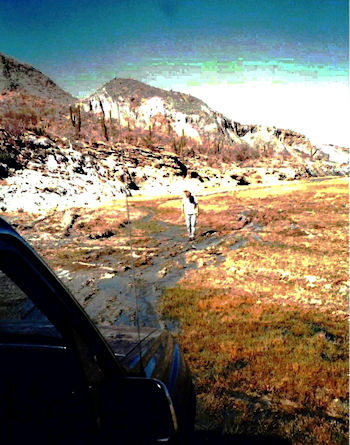

Ahead was a white limestone cliff from which water tumbled in small rivulets into a large, wide meadow, now swollen to a muddy swamp.

We stopped and got out. Tire tracks took off in several directions, their drivers obviously looking for the optimum spot to cross. Some got stuck and we could see where they had problems.

We tested the ground visualizing where each tire would go. Patches of solid earth could be found amid boulders and bushes. Ken then sped across the stream and parked on terra firma. The ground was crisp on top from the mineralized water. Like a pie crust it crunched when you walked.

We saw several springs bubbling up vertically to heights of three or four inches, creating crystal clear pools. However, it was salty and filled with bitter alkali.

The entire cliff had been formed by this alkali spring, and while water in the canyon above this spot was potable, down below the water brimmed with minerals leaving rings of white around former pools.

The deception of good water/bad water had earlier fooled the Jesuit missionaries. Back in 1753 Padre Fernando Consag made an exploratory trek into these northern wilds and noted available water at Calamajué.

Later Padre Wenceslao Linck, who established the San Borja Mission to the south in 1762, also explored the area and recommended Calamajué for the next mission site. It was about halfway between San Borja and an area called Velicatá which had a considerable indigenous population that could be converted.

Thus, in October 1766 Padres Victoriano Arnes and Juan Jose Diez arrived in Calamajué from San Borja. They were accompanied by 10 Spanish soldiers and 50 Indians led by Cochimi Chief Juan Nepomuceno. Even though the area was barren, they built structures on a rocky promontory and went about their work of trying to teach the local Indians their way of life.

They planted crops which subsequently died from the mineralized, salty water. After only a few months they were besieged by problems. Failing health forced Father Diez to leave. Locals revolted several times against Padre Arnes, but Chief Nepomuceno and the mission Indians helped put them down and punish them.

However, it was the bad water that forced them in May 1767 to relocate the mission to another remote arroyo, Santa Maria, after only seven months in Calamajué.

Historian Harry Crosby, in his epic trek up the El Camino Real for his 1974 book, The King’s Highway of Baja California, said upon reaching the water at Calamajué, “Each of the burros tried about one drink of it and rejected it entirely. I tasted it because Gerhard and Gulick’s book said it was safe, but, like the burros I saw no point in trying it again. The water had a strong bitter flavor and, in places where it had evaporated, it left accumulations of salt.”

A Remote Thoroughfare

We continued our journey down this canyon, so remote it seemed impossible to have been a major thoroughfare over 250 years ago.

After the road expands onto a broad wash it leaves the arroyo for a rocky mesa. A small, weathered sign, no longer readable, indicated the old mission. We hiked to the site, which featured only a few rock walls and mounds.

Since my last visit it appeared that someone had tried to excavate one of the wall mounds with hand tools. Also, some surveyors left their concrete markers on the four corners surrounding the site. I couldn't help but wonder if it would all be fenced to keep out those who would destroy historical areas.

We also explored the Molino de Calamajué, an abandoned gold ore mine on the lip of the opposite canyon wall near the road. Piles of rock outline the buildings and you can even see where a pulley or tram was located. An arrow scratched in concrete points across the arroyo to the mission site.

We continued to the gulf arriving at Campo Calamajué, a small, isolated fish camp on a wide sandy cove with rocky promontories at each headland. About 8-10 small fishermen’s shanties lined the cove. Pangas were neatly pulled up off the tide.

A few fishermen were repairing nets. Others were sitting in front of the shanties taking advantage of the mid-afternoon shade. The sun was shining brightly here without a single cloud to mar a perfect, baby blue sky.

There were about four or five families living at Campo Calamajué this mid-December, with about half the shanties vacant. We were invited to camp among them, so we pulled the truck up a respectable distance from the nearest dwelling.

The fishermen told us yellowtail and sierra can be caught from the shore. We tried and caught lots of the pesky bullseye puffers and some bass, but no sierra.

The water was so inviting I snorkeled a bit, seeing several schools of small fish and the puffers as well as one streamlined sierra mackerel with its distinctive yellow spots.

Then we saw fish boiling like crazy way out on the point. The piscatorial frenzy covered an area of about two football fields. We grabbed rods, extra hooks, and bait (frozen squid) and a few lures (Rapalas, Crocodiles and Candybars) and set off. By the time we hiked around the cove and scrambling over the rocks, they had already moved farther out. Missing the sierra bite, we did catch about a dozen nice triggerfish and a large parrotfish.

Later, as the enormous tide sucked much of the water from the delightful cove, darkness fell exposing a most unique phenomenon—the most dazzling display of phosphorus I'd ever seen.

We were rewarded with a luminescence that reminded us of black lights on white shirts in a disco. Even walking on the wet cobbles produced a bright display that looked like we were rolling sparklers. Waves way out over the rocks were lit up. It was eerie and beautiful but apparently not that unusual.

While we were drifting off to sleep, we heard the pangas take off for a night run. In the morning we were in awe as they were unloading about 800 pounds of sierra from their nets. One fisherman told me the fish follow the wake of phosphorous right into their nets. Sounded like a fish story to me, but with all their sierra I believed it.

***Please note that some of the roads featured in this article are not conventional roads and our insurance coverage would not apply. Our coverage is only valid on paved and dirt roads designed for the normal transit of vehicles.

I have used Baja Bound for insurance for many years. Their online process is easy and cost...

I'm listening to the audiobook of God and Mr. Gomez at this very minute. One of my favorite books....

Great insurance! Bought one year but was cured in 2 days on my visit to El Sauzal de Rodriguez next...